As a member of the skeptic/freethinker community, I tend to associate with many people that share my views on things. I am somewhat spoiled by the fact that most people my age in Canada read from the same playbook, and have many of the same fundamental assumptions/conclusions about the world. It is therefore usually a pretty big shock when I meet someone who is a 9/11 truther or a climate change denialist or a hardcore libertarian making themselves known at a skeptic’s pub night or related event.

Many people use the term ‘skeptic’ to denote anyone who ‘opposes the status quo’ – saying that their conspiracy mongering over who really took down the World Trade Center towers is just them being ‘skeptical’. When organized skeptics talk about ‘skepticism’, they generally refer to methodological skepticism – a philosophy wherein all beliefs and truth claims are subjected to scrutiny and apportioned to the available evidence. While superficially those do seem to overlap, the problem with the positions I mention above is that they fail to doubt their own truth claims, instead relying on a combination of ideological rigidity and back-filling to “prove” their validity. As I’ve spelled out before, it is no good to decide something is true and then look for evidence – the human mind is capable of thus “proving” pretty much anything it likes.

Enter “racial realism”.

Regular readers may recall a number of months ago when I had a white supremacist show up in the comments section. It triggered a somewhat unusual and surprising reaction in me – one that I myself wasn’t really prepared for. That aside, while I stand by my characterization of that person as a de facto white supremacist, he would probably prefer the term “race realist”. Race realism is, generally, the position that observable racial groupings are biologically valid, and are so beyond simply superficial cosmetic traits. The video linked above was created by someone who describes herself in such terms.

It may surprise you (it certainly surprised me) to learn that there are many points of agreement between myself and the author. Insofar as race has a biological component, I am certainly happy to admit that genetic differences account for phenotypic differences. I will also agree with her assertion that many people (most often those on the political left) misuse the term ‘racist’, often in an attempt to introduce emotional weight to an argument, sometimes in lieu of actually refuting the claims made. I will finally agree with her closing statement that noticing racial differences is not, in and of itself, racist.

That is probably the beginning and the end of the places where the author and I would agree with each other. The rest of the video is (despite the catchy musical accompaniment) is utter nonsense. Her basic position is that because races are inherently different, that “noticing” racial differences is only natural. The problem with her position specifically, and racial realism generally, is twofold. First, the statement that racial differences account for the type and magnitude of differences in access/achievement seen between racial groups is unsupported by the scientific evidence, and fails to take into account the multitude of other demonstrated, observed factors.

Second, the video uses the word “noticing” in a profoundly different way than we would colloquially. When the author uses the word ‘noticing’, she means semantically what most of us would use the word ‘explaining’ for. Noticing that there are disparities between racial groups is, indeed, not a racist action. Explaining differences between groups by attributing them to something as demonstrably superficial as race certainly qualifies as racism – almost by definition.

I’m not going to spend too much longer on the myriad of reasons why I disagree with the author. Friend of the blog Will has done an unbelievably thorough job of skewering the specific claims about race that the author makes:

Ruka also demonstrates a complete lack of understanding of social constructivism. The fact that race is socially constructed does not mean it is not real. It means that it is not reducible to biological traits. Race is a very real idea and has real, tangible implications on peoples’ lives. So, of course racial hate crimes exist, but they are based on the way people define race (e.g., skin color), not based on biology. I will close with a typically anthropological discussion. The definition of “race” varies cross-culturally, across time, and across space. This fact is evidence for a social construction of race. An excellent example of this can be seen in the changes of the race category of the United States national census over the last two centuries and in comparing the American categories of race options to the race options on other countries’ censuses.

Tim Wise has similarly taken his quill to the position of racial realism, saying that even if it was true it would be morally inarguable:

In other words, in order to uphold the notion that people should be treated like the individuals they are — not merely as individuals in the abstract — considering the way that racial identity may have limited opportunities for job or college applicants (and thus, taking affirmative action to look more deeply at what goes into an applicant’s presumed and visible “merit”) would be morally requisite. And yet, making assumptions about individual IQ based on group averages, and then doling out the goodies accordingly would be morally repugnant. Both look at group identity, but for very different reasons, with very different levels of ethical justification, and with very different practical results.

I don’t think I could do a better job than they have of taking on this absurd position. My utter contempt for it is such that I am loath to run the risk of elevating it above the adolescent brain-fart it is. What I would like to do is offer some perspective on why I think the author, and those like her, should be particularly addressed by the skeptical community.

Smart vs. intelligent

Back in early 2009, I re-posted a brief essay I had written delineating the concepts of “smart”, “wise”, “intellectual” and “intelligent”. I have a tendency to redefine terms for my own purposes, and I wanted that page to serve as a reference in case I ran into someone who objected to my describing of something as ‘stupid’. Simply put, “intelligent” refers to one’s ability to adapt to novel situations, “wise” includes the application of previously-held knowledge, and “intellectual” refers to one’s willingness to process things cognitively and through the application of logical processes. “Smart” is the confluence of all three of these attributes, whereas ‘stupid’ is its polar opposite.

I have no doubt that Ruka, the author of the video above, is intelligent. I am sure that, in her own way, she is “intellectual”, except insofar as she ignores contradictory evidence and refuses to address the flaws in her position, preferring instead to bloviate about how mean everyone is to her when she’s ‘just asking questions’. None of her intelligence, however, protects her from being profoundly stupid. I cannot really speculate about whether she is intentionally introducing straw man arguments and red herrings into her position, but I can conclude that, intentional or not, her arguments are sloppy and borne of an unbelievably arrogant reliance on her own perception of her cognitive abilities.

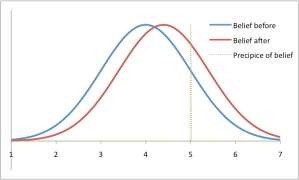

This kind of unwarranted self-assurance is also what is at play in 9/11 truthers, climate skeptics, Holocaust deniers, and other non-methodological ‘skeptics’. While it is most often an unfair straw man characterization foisted upon us by our opponents, it is also occasionally true of those who call ourselves ‘freethinkers’. Skepticism, as I’ve mentioned variously in previous posts, is an ideal to be pursued; not a goal to be reached. The only reliable path to truth is to test our beliefs against observed evidence, and (more importantly) to change them when necessary. While this can be done without ridiculous hang-wringing and false modesty, one must always keep in the back of their mind the statement “what if I’m wrong? How could that be demonstrated?”

Failing to do this, or only pretending to do it, as Ruka does (she apparently blocks comments unless they agree with her or insult her – presumably so she can paint her opponents as lunatics as she does in the video I link above), will inevitably lead us into positions like hers, where our inherent beliefs about the world are ‘justified’ through a convoluted process of back-filling and denial.

Like this article? Follow me on Twitter!